Understanding Recursive Ascent Parsers

Recursive ascent is an obscure parsing technique I researched about a few years ago. It’s an interesting approach to bottom-up parsing, the parsing method used by parser generators like Bison or ANTLR. If you’re familiar with recursive descent parsing, recursive ascent parsing is the bottom-up version of it.

Unfortunately, there isn’t a lot of material about it on the internet. When I first started learning about it, there was only one blog post about it.[1] There were also some academic papers about it, but these are very theory-heavy and difficult to read (at least for me).[2]

I’m writing this post to share what I’ve learned about recursive ascent parsing; how it works and how to implement it. I’ll assume you have some familiarity with recursive descent parsing, as it’s usually the first parsing technique people learn. If not, I recommend reading up on it first.[3]

The first half of this post will cover the theory behind bottom-up parsing, and the second half will delve into the code implementation of a recursive ascent parser.

Disclaimer: I’m not an expert. I didn’t take any classes on compiler theory and I haven’t read the dragon book. Please reach out If you noticed any mistakes in this post, especially in the first half!

Bottom-Up vs Top-Down Parsing

Parsing techniques can be roughly grouped into 2 types, top-down and bottom-up. Top-down parsers start from the highest level of the grammar rules, while bottom-up parsers start from the lowest level. Generally, top-down parsing algorithms are easier to understand and implement, but are less powerful and accept a smaller set of grammars than bottom-up algorithms.

A nice way to visualise the difference between top-down and bottom-up approaches, which I just found recently, is to correspond top-down parsing with the Polish notation, and bottom-up parsing with the reversed Polish notation.[4] In Polish notation, the operators come before the operands. In reversed Polish notation, it’s the opposite, the operands come before the operators.

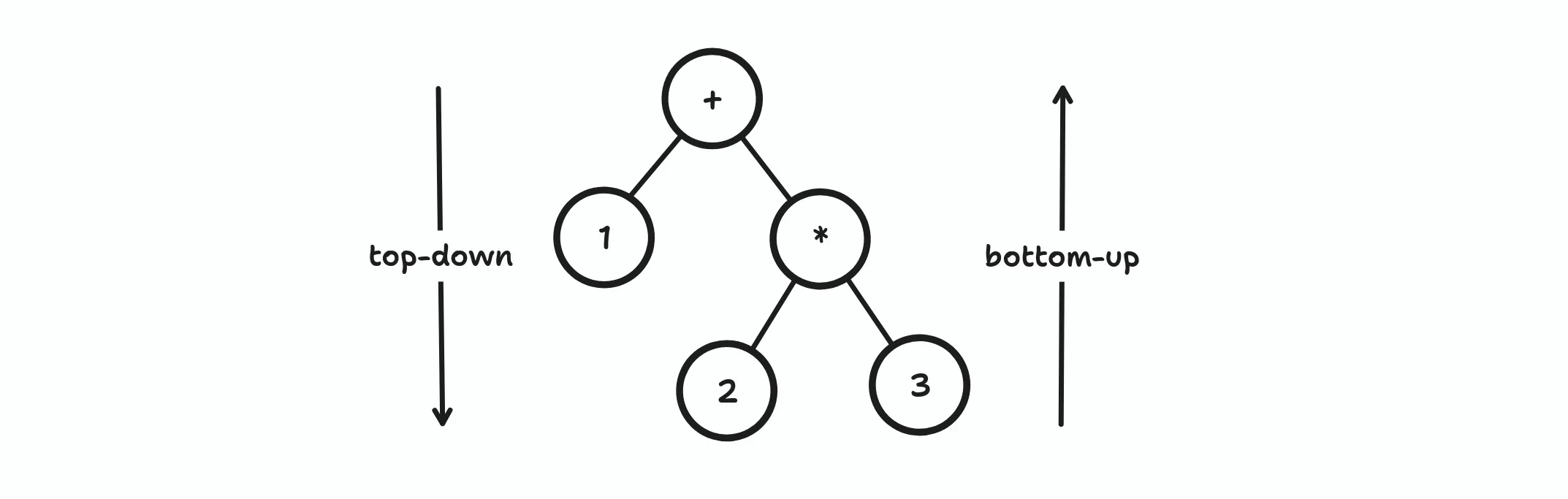

Let’s use this math expression 1 + 2 * 3 as an example. We can also represent this expression as a tree:

A top-down parser builds the parse tree starting from the root node and ending in the leaf nodes. In computer science lingo, this is also called a pre-order traversal. If you write down the nodes in the order it is traversed, you’ll end up with + 1 * 2 3, the Polish notation of the previous expression.

On the other hand, a bottom-up parser builds the parse tree starting from the leaf nodes up to the root node, aka, post-order traversal. The order the nodes are traversed will form the reversed Polish notation of the original expression: 2 3 * 1 +.

You’re probably already familiar with the top-down approach, as that is how recursive descent parsers work. Personally, I find it difficult to reverse this logic and understand how a bottom-up works. Unlike top-down algorithms, which determine what to do next based on the current grammar rule, how does a bottom-up algorithm know what rule it is in and what it should do next?

LR Algorithm

LR is a bottom-up parsing algorithm used in most parser generators. More accurately, it is a family of parsing algorithms that follow a similar approach. Recursive ascent parsers also use this algorithm. There are many variants such as LR(k), SLR, LALR, etc.,[5] but all of them are based on the same two fundamental actions: shift and reduce.

Shift means to advance or “shift” to the next token from the input stream. If the shifted tokens match one of the rules of the grammar, they will be converted or “reduced” into that rule. An LR parser will continue shifting and reducing until the entire input is consumed and transformed into a single parse tree. This concept may sound abstract, so let’s use an example to illustrate it.

We’ll use this grammar:

expr -> expr '+' term

expr -> expr '-' term

expr -> term

term -> INTEGERThis grammar defines a language that consists only of additions and subtractions of integers. The table below shows the actions an LR parser takes when parsing this input 1 + 2 - 3 according to the grammar above:

| Parse stack | Unparsed | Action |

|---|---|---|

| empty | 1 + 2 - 3 | Shift 1 |

| 1 | + 2 - 3 | Reduce term -> INTEGER |

| term | + 2 - 3 | Reduce expr -> term |

| expr | + 2 - 3 | Shift + |

| expr + | 2 - 3 | Shift 2 (because there are no rules that match expr ‘+’) |

| expr + 2 | - 3 | Reduce term -> INTEGER |

| expr + term | - 3 | Reduce expr -> expr ‘+’ term |

| expr | - 3 | Shift - |

| expr - | 3 | Shift 3 |

| expr - 3 | Reduce term -> INTEGER | |

| expr - term | Reduce expr -> expr - term | |

| expr | Accept |

Here, I used the term “parse stack” for the shifted inputs. That’s because most LR parsers use a stack to keep track of the shifted tokens. A shift is a push to the stack, and a reduce pops tokens that match a rule and push the corresponding rule to the stack.

How does the parser know which rule it should reduce to? Most LR parsers construct a parse table, which is a table of parser instructions based on the grammar. Entries in the table tell the parser whether to shift or reduce based on the current token in the input stream. The entire combination of actions a parser can take based on any input fits in this one table. This is possible because there are only a finite number of possible states an LR parser can assume for a given grammar. These are called the LR states.

Because the number of states is finite, an LR parser is essentially just a finite state machine (FSM) modelled after the LR states. The parse table contains the state transitions. The parse stack is used to keep track of the current state. In fact, parser generators are just programs that convert a grammar into a table-based state machine.

What about recursive ascent parsers then? A recursive ascent parser is just the “functional” version of a traditional LR table-based state machine. Instead of rows in a table, state transitions are encoded as functions. A function call is a shift action, and a reduce action happens when the function returns. The parse stack is the function call stack!!

I had an Aha! moment when I first realised this about recursive ascent parsers. This might not make sense now, but once we get to the code implementation, it will hopefully make this more clear.

Building the State Machine

Before getting into the code, first, we’ll need to understand how to generate a parse table. This is a process that is automated by parser generators, but in recursive ascent, we have to do this manually. The first step is to compute all the possible LR states for a given grammar, in other words, build a finite state machine. Again, we’ll use an example grammar to illustrate this.

We’ll modify the grammar from the previous section to support multiplications and drop subtractions:[6]

S -> expr eof

expr -> expr '+' term

expr -> term

term -> term '*' factor

term -> factor

factor -> INTEGERNote the extra rule S (start), which will be used for a reduction when the parser has accepted the whole input. eof indicates the end of the input stream.

Next, we’ll need to construct the LR(0) items, which are grammar rules with a dot (•) to mark the current position of the parser.[7] E.g., the rule S -> expr eof contains one LR(0) item: S -> • expr eof. Everything to the left of the dot has already been parsed or shifted.[8] For brevity’s sake, I’ll shorten “LR(0) item” to just “item” going forward.

For each item, we then need to compute its closure. The closure of an item is the set of all possible items that can be derived from applying the appropriate grammar rules to it. Here’s how it works:

- Start with a set of items. For our grammar, this will be

{ S -> • expr eof }. - For each item, if the symbol on the right of the dot is a non-terminal, expand its rules based on the grammar and turn the expanded rules into items by adding a dot. From our first item, we expand

exprintoexpr -> • expr '+' termandexpr -> • term. - Add the expanded items to the original set. Our set should now look like

{ S -> • expr eof, expr -> • expr '+' term, expr -> • term }. - Repeat steps 2 and 3 until no new items can be added to the set.

A non-terminal is any symbol that represents a grammar rule, e.g. expr, term, or factor. The opposite of this is a terminal, which is an actual value or token that is produced by the lexer, e.g. '+', '-', and INTEGER. If we apply closure to the first item in the grammar S -> • expr eof, we’ll end up with the first LR state:

# State 0

S -> • expr eof

expr -> • expr '+' term

expr -> • term

term -> • term '*' factor

term -> • factor

factor -> • INTEGERWe can then transition from this state into the other states by accepting different values and advancing the dot. The values that the parser can accept are the terminals and non-terminals on the right side of the dot. So, for state 0, the values it can accept are expr, term, factor, and INTEGER. Let’s say the parser receives an expr. This will become our second state:

# State 1 (State 0 + expr)

S -> expr • eof (Accept)

expr -> expr • '+' termWhen the dot reaches the end of the starting rule, it is called the accept state. It means that the input has been parsed fully and the parsing is complete. If we had instead received a term in the first state, then we’d end up with this state:

# State 2 (State 0 + term)

expr -> term •

term -> term • '*' factorAnd we just repeat this process until all dots are at the end of each rule. There is an exception to this though, which I’ll get to in a bit. Anyways, here are some more states:

# State 3 (State 0 + factor)

term -> factor •

# State 4 (State 0 + INTEGER)

factor -> INTEGER •

# State 5 (State 1 + '+')

expr -> expr '+' • term

term -> • term '*' factor

term -> • factor

factor -> • INTEGER

# State 6 (State 2 + '*')

term -> term '*' • factor

factor -> • INTEGER

# State 7 (State 5 + term)

expr -> expr '+' term •

term -> term • '*' factorNow, it might make sense to do this for the next state:

# State 8 (State 1 + factor)

term -> factor •Notice that this is the same state as state 3. If we encounter a state that we have seen before, we don’t have to create a new state. Instead, we’ll just jump or goto the state that we’ve already found before. This will make more sense when we build the actual parse table. Now, let’s finish the last state.[9]

# State 8 (State 6 + factor)

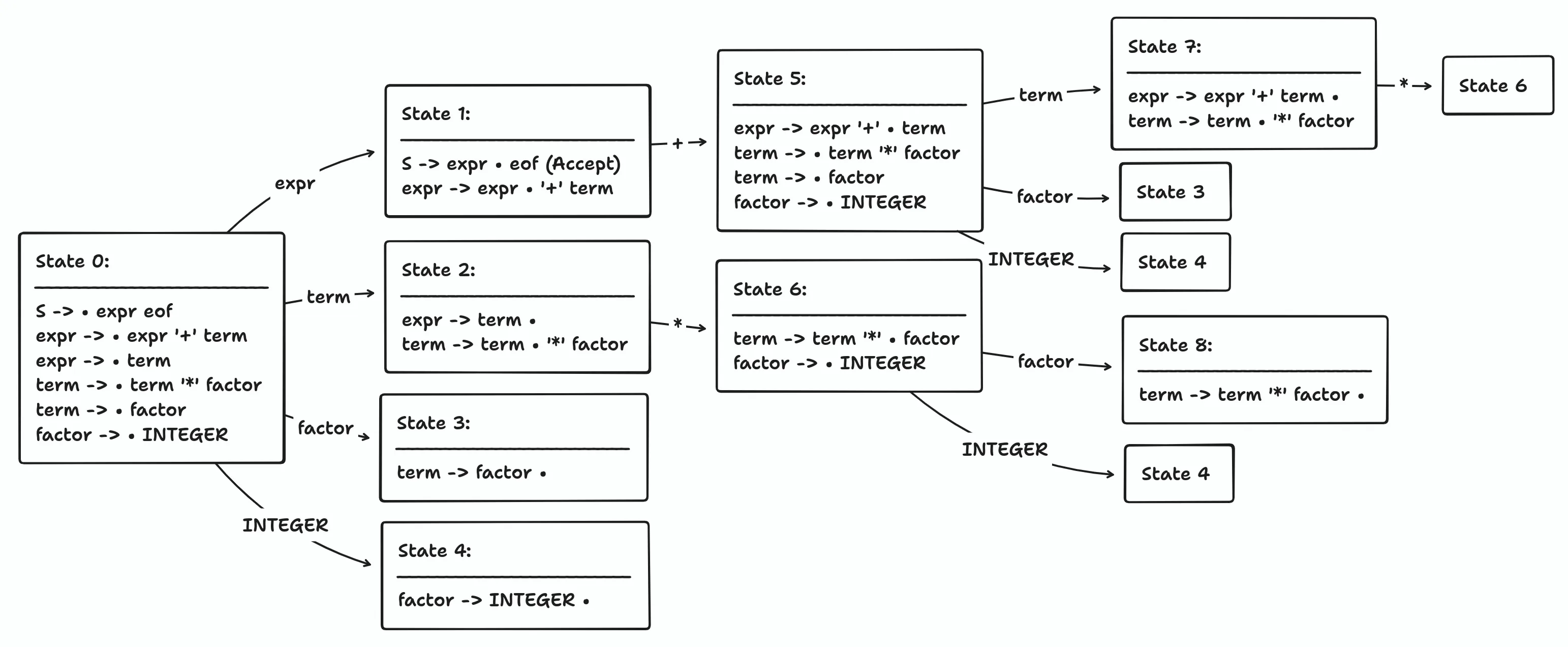

term -> term '*' factor •And we’re done! Here’s a diagram to help you visualise the state transitions:

The Action and Goto Table

Now that we have the state machine, we can translate it into the parse table. A transition between states represents a shift action. Items with a dot at the end represent reduce actions. The parse table consists of two parts, the action table and the goto table. The action table tells the parser whether to shift or to reduce based on a lookahead terminal. The goto table tells the parser which state to go to given a non-terminal. Here’s what the action and goto table looks like for our grammar:

| Action | Goto | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | + | * | INTEGER | eof | expr | term | factor |

| State 0 | s4 | gt1 | gt2 | gt3 | |||

| State 1 | s5 | Accept | |||||

| State 2 | r3 | s6 | r3 | r3 | |||

| State 3 | r5 | r5 | r5 | r5 | |||

| State 4 | r6 | r6 | r6 | r6 | |||

| State 5 | s4 | gt7 | gt3 | ||||

| State 6 | s4 | gt8 | |||||

| State 7 | r2 | s6 | r2 | r2 | |||

| State 8 | r4 | r4 | r4 | r4 |

Each row represents a state in the state machine, each column in the action table represents a terminal, and each column in the goto table represents a non-terminal. sN means “shift and go to state N”, rN means “reduce using rule N”, and gtN means “go to state N”. Unlike shift, goto doesn’t take in a token from the input stream and just transitions to the next state.

Here are the grammar rules again for reference, with the rule numbers added for reductions:

1. S -> expr eof

2. expr -> expr '+' term

3. expr -> term

4. term -> term '*' factor

5. term -> factor

6. factor -> INTEGERThe parse table is usually much larger than the grammar, and languages with a complex grammar will produce huge tables which are almost impossible to compute by hand. This is why people create parser generators. Based on how the states and parse table are generated, the resulting parser can be called either a simple LR (SLR), look-ahead LR (LALR), or a canonical LR parser (LR(k)). I’m not going to go into detail about these algorithms here, as it can lead to a rabbit hole. Just know that we have a working LR(0) parse table now.[10]

The next step of the LR algorithm is to run the actual parser using a real input. Traditional LR parsers will run a loop and parse a token stream following the rules of the parse table. In our case, we’ll implement this mechanism as mutually recursive functions.

Writing The Parser

At this point, we’re ready to build the actual parser. I’ll be writing the code in Python because it’s easy to read. To make sure our parser is correct, we’ll also implement an interpreter for the expressions we parsed. First, let’s start with the program’s entry point:

import sys

def main():

if len(sys.argv) != 2:

print("usage: {} [STRING]".format(sys.argv[0]))

return

tokens = lex(sys.argv[1])

ast = parse(tokens)

result = evaluate(ast)

print(result)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()This program will receive a string as an argument and print out the evaluated string. Don’t worry about the unimplemented functions for now. We’ll get to them soon.

A Simple Lexer

Since we don’t have a complex grammar, our lexer can just scan tokens separated by whitespace. This works but it also means that we need to separate the terminals in our input string with spaces. A better lexer knows whether a token can be scanned regardless of whitespaces.[11]

def lex(string: str):

return string.split()Representing the Abstract Syntax Tree (AST)

We’ll also need a type to represent the AST that will be produced by the parser:

class AST:

def __init__(self, left: "AST | None", right: "AST | None", value: str, kind: str):

self.left = left

self.right = right

self.value = value

self.kind = kindIf you’ve noticed, the AST class above looks like a binary tree. That’s because all the expressions we have are binary operations, which can be represented as a binary tree. The final AST should look like this diagram from an earlier section. For more complex grammars, you might need to use a more complex data structure for the AST.

Converting the Parse Table into Functions

Our parse function will start from the first state. If you recall the previous parse table, there are 4 possible actions the parser can take:

| Action | Goto | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | + | * | INTEGER | eof | expr | term | factor |

| State 0 | s4 | gt1 | gt2 | gt3 |

We can translate this to code like so:

def state0(tokens: list[str]):

token = peek(tokens)

if token.isdigit():

# shift token, move dot forwards

tokens = tokens[1:]

# go to state 4

ast = state4(token)

else:

panic(token)

if ast.kind == "factor":

# go to state 3

ast = state3(ast)

if ast.kind == "term":

# go to state 2

ast, tokens = state2(ast, tokens)

# go to state 1

return state1(ast, tokens)

def parse(tokens):

return state0(tokens)Note, we don’t actually need to check the ast.kind here because if ast = state4(token) succeeds, then we’re guaranteed to get a factor. The same goes for ast = state3(ast), which is guaranteed to return a term. So, we can rewrite state0 like this:

def state0(tokens: list[str]):

token = peek(tokens)

if token.isdigit():

# shift token, move dot forwards

tokens = tokens[1:]

# go to state 4

ast = state4(token)

else:

panic(token)

# go to state 3

ast = state3(ast)

# go to state 2

ast, tokens = state2(ast, tokens)

# go to state 1

return state1(ast, tokens)Here are the helper function definitions. peek returns the next token, while panic prints an error message if an unexpected token is found and terminates the program:[12]

def peek(tokens: list[str]):

return "" if len(tokens) == 0 else tokens[0]

def panic(token: str):

print("unexpected token: {}".format(token))

exit()As mentioned before, reduce happens when returning from a function:

| Action | Goto | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | + | * | INTEGER | eof | expr | term | factor |

| State 3 | r5 | r5 | r5 | r5 | |||

| State 4 | r6 | r6 | r6 | r6 |

def state3(ast: AST):

# reduce using rule 5: term -> factor

return AST(ast.left, ast.right, ast.value, "term")

def state4(token: str):

# reduce using rule 6: factor -> INTEGER

return AST(None, None, token, "factor")Now here’s where things get more interesting:

| Action | Goto | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | + | * | INTEGER | eof | expr | term | factor |

| State 1 | s5 | accept | |||||

| State 2 | r3 | s6 | r3 | r3 |

def state1(ast: AST, tokens: list[str]):

# loop to handle left recursion

while peek(tokens) == "+":

# shift token

tokens = tokens[1:]

# go to state 5

ast, tokens = state5(ast, tokens)

# accept

return ast

def state2(ast: AST, tokens: list[str]):

while peek(tokens) == "*":

tokens = tokens[1:]

ast, tokens = state6(ast, tokens)

# reduce using rule 3: expr -> term

return AST(ast.left, ast.right, ast.value, "expr"), tokensThe grammar we used has rules that contain left recursion. This happens when a rule starts with a symbol that is itself, e.g. expr -> expr '+' term and term -> term '*' factor. Top-down parsers can’t handle this type of grammar. If you’ve implemented a recursive descent parser before, a left-recursive rule will cause the parse function to immediately call itself before doing anything else, leading to infinite recursion and a stack overflow.

When using top-down parsers, you have to refactor the grammar to be right-recursive or tail-recursive. LR parsers can handle left recursion just fine, so this isn’t a problem for us. We can use a loop and a condition to check whether the recursive calls are done.

In state 1 and state 2, the parser has parsed the left side of the binary operation. In the next states, the parser will parse the right side of the binary operation:

| Action | Goto | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | + | * | INTEGER | eof | expr | term | factor |

| State 5 | s4 | gt7 | gt3 | ||||

| State 6 | s4 | gt8 |

def state5(left: AST, tokens: list[str]):

token = peek(tokens)

if token.isdigit():

tokens = tokens[1:]

right = state4(tokens)

else:

panic(token)

right = state3(right)

return state7(left, right, tokens)

def state6(left: AST, tokens: list[str]):

token = peek(tokens)

if token.isdigit():

tokens = tokens[1:]

right = state4(tokens)

else:

panic(token)

return state8(left, right), tokensOnce the right side is parsed, we can then reduce these rules in state 7 and state 8:

| Action | Goto | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | + | * | INTEGER | eof | expr | term | factor |

| State 7 | r2 | s6 | r2 | r2 | |||

| State 8 | r4 | r4 | r4 | r4 |

def state7(left: AST, right: AST, tokens: list[str]):

while peek(tokens) == "*":

tokens = tokens[1:]

right = state6(right, tokens)

# reduce using rule 2: expr -> expr '+' term

return AST(left, right, "+", "expr"), tokens

def state8(left: AST, right: AST):

# reduce using rule 4: term -> term '*' factor

return AST(left, right, "*", "term")And that’s all of the code for the parser! Now we just have to check whether the output is correct. Let’s add a method in the AST class to pretty-print itself, so that it’s easier to visualise:

class AST:

# ...

def pprint(self):

if not self.value.isdigit():

print("( {} ".format(self.value), end="")

else:

print(" {} ".format(self.value), end="")

if self.left:

self.left.pprint()

if self.right:

self.right.pprint()

if not self.value.isdigit():

print(" )", end="")I’m printing the AST as s-expressions so that it’s easy to see the expressions follow the correct operator precedence.[13] Given an input like 1 + 2 * 3 + 4, this method will print out the following: ( + ( + 1 ( * 2 3 ) ) 4 ). This looks right. All that’s left now is to implement the evaluate function and test if it works as expected.

Interpreting the AST

Here’s the evaluate function:

def evaluate(ast):

if ast.value == "+":

return evaluate(ast.left) + evaluate(ast.right)

elif ast.value == "*":

return evaluate(ast.left) * evaluate(ast.right)

else:

return int(ast.value)It will recursively evaluate all the nodes in the AST. Let’s run the program and check if the output is correct:

$ python3 recursive-ascent.py '1 + 2 * 3 + 4'

# 11Good, it works! Now let’s write some generated tests to have more confidence in the program. Here’s a function that would generate random numbers and combinations of operators (+ and *), run the evaluate function on them, and compare the result to Python’s eval function:

def tests():

errors = 0

for _ in range(1000):

k = random.randint(2, 10)

nums = [str(i) for i in random.sample(range(10_000), k)]

ops = [random.choice(["+", "*"]) for _ in range(k - 1)]

expr = [i for j in zip(nums, ops) for i in j] + [nums[-1]]

input = " ".join(expr)

res = evaluate(parse(lex(input)))

py_res = eval(input)

if res != py_res:

print("incorrect output for:", input)

print("got:", res)

print("expected:", py_res)

errors += 1

if errors == 0:

print("all tests passed!")

# also some changes to main to allow users to run the tests

def main():

if len(sys.argv) != 2:

print("usage: {} [STRING]".format(sys.argv[0]))

return

input = sys.argv[1]

if input == "test":

tests()

return

tokens = lex(input)

ast = parse(tokens)

result = evaluate(ast)

print(result)The eval function will run any Python expression. Since Python can also evaluate math expressions, we can use it as a reference to verify the correctness of our evaluate function. If you run python3 main.py test, you should get this output: all tests passed!.

End

And that’s all. You can find the complete code on this GitHub repo. Hopefully, you have a good idea of how LR and recursive ascent parsers work now. You probably won’t ever use this technique when building a real compiler, but at least you learned something new. If you’d like to learn more about this topic or explore other parsing techniques, check out the links in the footnotes.

This blog post by Russel Johnston about implementing a JSON parser in Rust using recursive ascent really helped me when I first started. It’s probably the only blog post about recursive ascent on the internet besides this one. ↩︎

Here are some papers about recursive ascent parsers that you could read if you’re interested in the theory. ↩︎

Crafting Interpreters is a really good introductory book on writing compilers, and their section on parsing is all about implementing a recursive descent parser. It’s also probably the most influential book in my programming journey. I learned a lot from it, which I applied in areas other than in writing compilers. Highly recommend reading it if you’re in software engineering. ↩︎

I found this analogy from this blog post by Josh Haberman. He went deep into the details of both LL and LR algorithms in his blog post while keeping it easy to read. ↩︎

Here’s a nice overview of parsing algorithm literature you can explore if you are interested in the different variants of LR. ↩︎

This is done to show that the parser can handle operator precedence based on the grammar rules. Subtraction is removed to keep the section short and readable. The number of possible states will grow exponentially the more complex your grammar is. This is why it is inconvenient to write a bottom-up parser by hand, and why people create parser generators. ↩︎

A grammar rule is often called as a “production” in academic literature. I just use the term “grammar rules” because it’s more intuitive. ↩︎

My explanation of the algorithm for creating the parse table might not click with you, so here are some other resources you can read if you’re still confused. ↩︎

Note that the order of the states doesn’t matter. The parser will still work if the states were created in a different order, e.g. state 1 = state 0 +

term. ↩︎You can read more about why this is on this Wikipedia page. It should be a good starting point to explore the different variants of LR and the types of parse conflicts. For this article, I intentionally chose a grammar that is accepted by LR(0) to keep it simple. ↩︎

You can read Crafting Interpreters for a better idea of what production lexers do. ↩︎

This is a very basic approach to handling parse errors. Production-grade parsers will usually report errors, ignore them, and continue parsing. This is to catch as many errors as it can so that the programmer doesn’t have to recompile to find more errors. ↩︎

What better way to visualise AST than with s-expressions? When you read a lisp program, you’re looking directly at the program’s AST, which is just a lisp data structures! This is what clojurists often mean when they say “It’s just data”. ↩︎

Hi 👋. If you like this post, consider sharing it on X or Hacker News . Have a comment or correction? Feel free to email me or tweet me. You can also subscribe to new articles via RSS.

Continue reading: